- Home

- Ellis Weiner

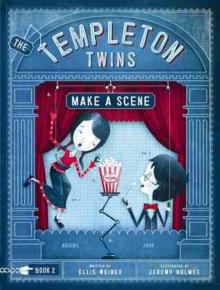

The Templeton Twins Make a Scene

The Templeton Twins Make a Scene Read online

TO MR. LEMONY SNICKET, ASSUMING HE IS A HE —ELLIS WEINER

TO MEGAN, PAXTON, AND CHARLIE —JEREMY HOLMES

Text © 2013 by Ellis Weiner.

Illustrations © 2013 by Jeremy Holmes.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4521-2989-1

The Library of Congress has catalogued the previous edition as follows:

ISBN 978-1-4521-1184-1

Design by Sara Gillingham Studio.

Typeset in Parcel, Chronicle Text, and Chevin.

The illustrations in this book were rendered digitally.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street, San Francisco, California 94107

Chronicle Books—we see things differently.

Become part of our community at www.chroniclekids.com.

A HANDWRITTEN NOTE OF APOLOGY

A NOTE TO THE READER ABOUT THE NOTE OF APOLOGY

Dear Reader:

I was going to start this book with a note of apology, written with my own hand. I was going to say how sorry I was if, while you are reading this book, you find yourself dismayed at having NOT read the book that comes before it, which is called The Templeton Twins Have an Idea. (And which for my convenience shall, from now on, be referred to as TTTHAI.)

However, I have decided not to apologize to you. In fact, I have decided that it is you who should apologize to me. My work in narrating this book would be much easier if I could be sure that you had read the first book.

If you had, you would know who (almost) everyone is. You would know what Professor Elton Templeton does. You would know in what ways Cassie, the Templetons’ dog, is ridiculous. And you would of course know what an excellent narrator I am, and thus be prepared to enjoy still more excellence in narration.

But since some of you haven’t read TTTHAI, I shall have to introduce all these things to you. I suggest, therefore, that those of you who haven’t read the first book write me an apology. You may use the following as a model, or use your own wording, so long as it is deeply apologetic.

Dear Narrator:

Please accept my (most humble apology/heartfelt expression of remorse/deepest sentiments of sorrow) for not having (read with uncontainable glee/thoroughly enjoyed at least twice/devoured in a single sitting) your previous narrative, THE TEMPLETON TWINS HAVE AN IDEA (TTT HAI).

I (have no one to blame but myself/know full well the disgraceful nature of my neglect/solemnly promise never to allow such an oversight to happen again).

Yours truly in true apology,

The Reader

Do I accept your apology? I think we can all agree that I cannot. The damage (to my feelings) is done. Let’s move on.

INTRODUCTION

Allow me to introduce myself. I am—as you already know—the Narrator. And allow me to introduce you. You are—as I already know—the Reader. I knew I would see you again, although of course I may never have seen you before and, whoever you are, I can’t actually see you.

This book is Number 2 in a series of books about the Templeton twins. If you have read book Number 1, then you already know two important things: a) that I was forced to write the first book against my will; b) that I am, similarly, being forced to write this one even though I don’t particularly feel like it; and c) that there is no “c)” because I said two things.

In the pages to follow you will encounter:

1. ABIGAIL AND JOHN TEMPLETON—A.k.a. (which means “also known as”) the Templeton twins. They are thirteen years old. They are not identical twins (who look very, very much alike, but are always of the same gender), but fraternal twins. They look like brother and sister, which is an excellent thing, because that is what they are.

2. PROFESSOR ELTON TEMPLETON—He is the twins’ father as well as a world-famous inventor of clever and occasionally useful devices.

3. CASSIE THE RIDICULOUS DOG—Cassie is a smooth-haired fox terrier, all white except for bits of black and brown here and there. She has little triangular ears and a tail that is the size and shape, but not the color, of a carrot. She is, like most fox terriers, insane.

4. DEAN D. DEAN AND DAN D. DEAN—These brothers, as it happens, are identical twins. They are about thirty-three years old. Dean D. Dean is extremely handsome and wears elegant clothing. Dan is not quite as handsome—“identical,” when used to describe twins, means very similar, but not exact copies of each other. Unlike his brother, Dan dresses normally, whatever that means. Dean—as you will soon see—is the more “dynamic” of the two, which is a polite way of saying that he is the bossier one.

Readers of the first book will be deliriously happy to encounter these people again in this book. However, if they hoped (because they loved the first book so very much) that the entire story of this book would be the same as the story in the first, they will be disappointed.

They’re not the only ones. I’m disappointed, too. I would much rather copy, word for word, the first book, than have to think of an entirely new series of words for the second book. But, sadly, I have no choice. I hope you appreciate all the trouble I’m going to, thinking up and writing down all these new words. But I doubt that you do.

This, then, completes the Introduction. I hope you enjoyed it. (Although do I? Really? Probably not.) The important thing is, you will by now have noticed what is not here.

AFTERWORD TO THE INTRODUCTION

WHAT IS NOT HERE

What is not here is a summary of the things that happened in TTTHAI. If you have not read the first book, or if you have read it but forgotten what was in it, then you do not know:

1. Why Dean D. Dean hates Professor Templeton.

2. How the twins acquired Cassie, the Ridiculous Dog.

3. What the specific hobbies of the twins are.

4. The details concerning the Professor’s Personal One-Man Helicopter (POMH).

5. All the brilliantly clever ways Abigail and John thwarted (yes, “thwarted.” This is an excellent word and you should make use of it in your daily life, as I do.) Dean D. Dean and Dan D. Dean.

6. Who did what and said what to whom, when, why, and how.

For information regarding these very important matters, I suggest you turn to the Appendix. “But Narrator,” I can imagine some of you objecting. “We thought an appendix was a little thingie in your body that sometimes has to be removed. A book can’t have an appendix! Does it, like, have, like, a kidney, too?”

Please. I am not impressed by your sarcasm. It is true that there is such a thing, in the human body, as an “appendix.” It is a small organ near the . . . well, near the other, more important organs. Whereas an appendix in a book is a section at the end of the book that provides some useful background information. In fact, a book can have more than one appendix. These are two ways in which the book-appendix is different from the human-body-appendix. Isn’t that interesting? Just take my word for it. It is. Now let us begin the second book itself.1

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Where is your appendix?

Are you sure? Are you sure you didn’t leave it in your “good” jeans?

Yes or Yes: The Narrator, to no one’s surprise, is off to a fine—no, an excellent—start.YY

1. But first: I assume that there will be readers who are too lazy, impatient, or rude to read the various Introductions. They will, therefore, not have read this footnote, which you—because you are an excellent and thorough reader—are reading at this very moment. As a reward, I am going to share with you the following important information: The first two paragraphs of Chapter 1 describe incidents that did not, in fact, take place.

>

Won’t it be fun to see the faces of those who could not be bothered to read the Introductions when they find out how they have been fooled? (Actually, I have no idea whether it will be fun or not. I won’t be there to see their faces when they read—and believe—those first two paragraphs of Chapter 1. If you are there, and it is fun, let me know.)

Oh, no, John!” cried Abigail Templeton to her brother. “Six dancing dinosaurs have kidnapped our dog, Cassie, and taken her to Paris, France!”

“We must thwart them at once, Abby!” replied John. “But first I must have my appendix removed!”2

The Templeton twins had been living in their new house for about a week, doing all the things they usually did—going to school and coming home, completing their homework, pursuing their hobbies, caring for Cassie (their ridiculous dog), and making meals—before Saturday finally came, and their father, the famous Professor Elton Templeton, was able to give them a tour of the college where he had recently started working.

So, after a breakfast of waffles and bananas, the twins climbed into the car, along with their (still-ridiculous) dog, and their father drove them to the campus.

Now, if I know you, you are wondering: “What took the Professor so long to show the twins around?” I’ll tell you, because you deserve to know. Well, wait. I’m not so sure you do deserve to know. But I will tell you anyway, as a favor. Then you’ll owe me a favor.3

The Professor had been unable to give the twins a tour of the new college right away because it was very important that he get to work immediately. Over the past few years, the college had not had enough students, and so was in danger of going out of business. The college had hired Professor Templeton and given him an urgent, vital assignment: to create an invention that would be so wonderful and remarkable and splendid that colleges and universities all over the world would want to buy one for themselves. Money from those sales would make it possible for the Professor’s college to remain in business.

And so, for the first week, the Professor did nothing but attend meetings and think of ideas and work calculations and sketch out basic designs for a new invention.

The name of the college was the Thespian Academy of the Performing Arts and Sciences. People called it TAPAS, for short. Now, I happen to be one of the few people who know that the word “tapas” is a Spanish word for a series of appetizerlike snacks served in small portions on small plates at bars and restaurants—very often, in world-famous Spain itself.

In this case, however, the name TAPAS is what we call an “acronym,” which is a made-up word formed by the first letters of a chain of words or names. For example, FAQ is an acronym for Frequently Asked Question.4 Similarly, TAPAS is an acronym for the Thespian Academy of the Performing Arts and Sciences.

Yes, I know: The first letters of “of” and “the” and “and” do not appear in TAPAS. That is often the case: The first letters of unimportant or inessential words often do not appear in acronyms. This is perfectly normal and nothing to be upset about.

This college was devoted to teaching acting, singing, dancing (or “dance,” as people who dance refer to dancing), and the many other important crafts and technical skills related to performances of all kinds.

Each building resembled an object or a symbol that was in some way connected with that department’s art or craft or skill. For example, the Department of Acting occupied two buildings that were shaped like the famous dual—one might even say “twin”—masks of Comedy and Tragedy that are commonly used to symbolize Drama. The Department of Script Writing was in the form of an immense typewriter. The Department of Wardrobe was shaped like a gigantic armoire.5 And so on.

“Look at these statues,” said Abigail Templeton as she, her brother, their father, and their notably silly dog strolled around campus. “They look kind of . . . tired.”

It was true. The central quad (“quad” is what colleges insist on calling their big, grassy yards) and many of the spaces between the buildings were decorated with statues of actors, singers, dancers, directors, playwrights, gaffers, grips, d-girls, and best boys.6 But all the statues were chipped, or rusted, or had pieces missing.

The Professor nodded. He said,

THIS PLACE IS IN TROUBLE. THAT’S WHY WE’RE HERE.

It was while the Templetons had paused near a statue of William Shakespeare that a man wearing sunglasses and a bushy beard suddenly encountered the family. He carried a single folded sheet of yellow lined paper. He stopped for a moment and seemed startled. Then he quickly looked away and, with a busy air, marched off.

John watched the man stride across the quad. “That guy looks familiar,” he said.

“You know,” the Professor said. “A lot of actors teach here. You may have seen him in a movie or on TV. Anyway, my workshop is just over there. In the Department of Lighting.”

The Professor led the twins and their always-thrilled-with-everything dog in the direction that the mysterious man had gone. As they walked, Cassie wagged her tail like crazy and panted and looked around as though walking past a building was the most exciting event of her life, and the Professor explained his latest invention.

“What is the difference,” he began, “between a play—or a musical, or an opera—and a movie or a television show?”

Abigail said, “A play is live.”

“Television shows can be live,” John said. “News is live. So are sports.”

“You’re both right,” the Professor said. “But even live television shows use something that plays can’t use.”

The twins traded a look that said, wordlessly, “Wait. We know the answer to this.”

“Cameras,” they both said at the same time.

“Excellent,” the Professor said. “And what do cameras permit us to do that we simply cannot do in a live performance onstage?”

The twins thought about that. So let’s all think about that as well, by which I mean, let’s you think about it.

Waiting for you to think about it . . .

Come on, we don’t have all day.

All right, I will give you a clue. But not just any clue. This clue will take the form of a cryptic crossword clue, because cryptic crossword puzzles were Abigail’s hobby (AYWKIYHRTTTHAI).7

Cryptics (as they are called) are different than regular crossword puzzles. The clues themselves are little puzzles. There are certain rules that most cryptic clues follow, one of which is that the definition of the word (or phrase) is either at the beginning or the end of the clue. The rest of the clue is the puzzle you have to solve. (Cryptic clues also tell you how many letters are in the word, or words, which make up the answer.)

Thus, a cryptic clue might be “Hateful dance? It’s only a game (8).” You would know, from this, that the answer is one word, with eight letters, which literally means either “hateful dance” (whatever that can possibly mean), or “It’s only a game.”

I shall place the solution to this clue in a footnote.8 By this, I do not mean that I will come to your house and attach a note with the answer on it to your foot. I mean I will place the answer at the bottom of the page. But before looking at it, first try to figure it out.9

The cryptic clue for the answer to the Professor’s question is: Nutty cups lose pictures from very near (5-3)

Words like “nutty” or “crazy” signal you to recombine the letters of the words before or after. The numbers tell you that the answer consists of a five-letter word and a three-letter word joined by a hyphen.

If you can’t figure out the answer (or if you can’t be bothered to try), you may look at the bottom of the page if you wish.10

Where were we? Ah, yes: The twins were trying to tell their father what it is that cameras allow us to do that we can’t do in a live performance.

Without much confidence, Abigail guessed, “The camera can record it so that people can watch it later?”

“Or,” John added, “show it in black and white, if you want to, instead of color?”

“Those are g

ood ideas,” the Professor said. “But that’s not what I’m getting at. I’ll give you a hint. This is something so obvious that it might be very hard to see.”

Does that hint shock and surprise you, reader? Oh, I think it does. Because how can something be so obvious that you can’t see it? “Obvious” means “easy to see.” But sometimes, especially when we’re looking for something that we think is tricky, we may see the obvious things, but we skip over them. We think to ourselves, “I know that what I’m looking for is tricky and hard to see. So this obvious thing can’t be it.”

Except sometimes it is.

“The answer,” the Professor said, “is that cameras let us use close-ups. The camera lets us move in close to an actor’s face, or hand, or foot, or an object—whatever we want the audience to be sure to see. We can fill the whole screen with it. You can’t do that on a stage.”

Thus, if you get “nutty” with (i.e. rearrange the letters in) “cups lose,” you will find that the answer is:

The Professor paused and then said, somewhat dramatically, “And that is what this college wants me to do. To create a way to show close-ups onstage.”

Now, if the Professor had said this to you, or even to me, we would have stopped dead in our tracks, and stared back at him with wild, bulging eyeballs, and trembled in terror, and clutched our hair and pulled it out in fistfuls, and cried, “BUT SUCH A THING IS IMPOSSIBLE! HOW WILL YOU EVER SUCCEED AT MEETING SO OVERWHELMING A CHALLENGE?” All right, perhaps I am exaggerating slightly. I myself would not behave in this way. But I’m sure you would have.

But neither you nor I are the Templeton twins, who were long used to hearing about their father tackling this or that impossible-seeming task.

The Templeton Twins Make a Scene

The Templeton Twins Make a Scene